Most of us should be deadlifting. And by most of us, I mean all of us. We should follow the novice progression, deadlifting every day. Then alternate in power cleans, then chin-ups. After that probably some sort of heavy-light-medium variation. Or, if you have access to your youth, whole milk, and XY chromosomes, the Texas Method. If you have moved beyond weekly progressions, then you have probably been exposed to the rack pull, maybe paused deadlifts, and if you have offended your coach, haltings. At some point in your intermediate to advanced programming it might behoove you to introduce other deadlift variations.

These children of the parent movement can serve multiple purposes. If there are egregious technique errors, then it is almost always better to reduce weight and get the conventional deadlift correct. However, there are times when assistance movements might be helpful. A paused deadlift, for example, may teach a lifter to extend his knees before the hips, maintain shoulder extension, and keep his back set in rigid extension in the first part of the pull.

A paused deadlift could spread out the stress-recovery-adaptation cycle – it is artificially felt to be heavy (because of the pause) even though it is necessarily lighter (because of the pause). In this way, an athlete can deadlift, but not at a load that will produce as much systemic stress as a conventional deadlift. And sometimes, when things line up, an introduction of the variation could serve both purposes of addressing technique while also spreading out stress – it takes some skill and experience on the part of the coach for it to work out this way.

Here, I would like to examine the snatch-grip and the deficit versions of the deadlift. They both must be lighter because of the increased range of motion, but in quite different ways.

The Snatch-Grip Deadlift

The hallmark of the snatch-grip deadlift is just that– the snatch-grip, called thus for the wide grip taken on the bar that resembles the Olympic snatch. The wide grip, the abduction of the arms as seen from the frontal plane, means that there is contractile force from the lats both keeping the bar over mid-foot and keeping the arms from adducting to plumb. This means that the athlete will have to pull the bar much harder into their legs, which might be a beneficial variation for teaching athletes to use their lats during the pull.

Josh Wells trains the snatch-grip deadlift at Starting Strength Katy. (Credit: Shelley Wells)

This also means that

the hips will be much higher in the setup, closing the hips angle and

opening the knee angle – like a snatch start position. Even with

this anatomical manipulation, the hamstrings remain in isometric

contraction at the start of the pull since the knees are opened to

the extent the hips closed, as in the conventional deadlift.

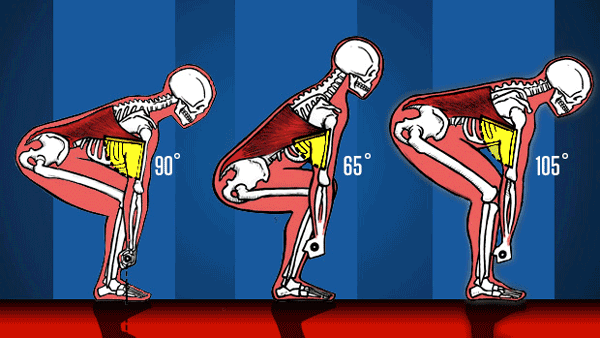

Angle of the lats with the hips at correct (left) and incorrect heights (center, right). (Adapted from Starting Strength: Basic Barbell Training, 3rd ed)

The image on the far right might be the hip height or the start

position of the snatch-grip deadlift (more closed), but because of

the wider grip, the knees will need to be bent further, as in the

middle image. A correct set-up puts the hamstrings in isometric

contraction at the start as well as the lats angled to insertion at

90 degrees from their origin, the strongest angle for them to pull to

keep the bar over mid-foot. Just like the hamstrings reaching further

than ideal extensibility in the far right image, and less so in the

middle image, the lats too will be brought into isometric contraction

with the higher hips and more bent knees.

The grip width need not

be your actual snatch grip width in an attempt to mimic your snatch

(your hip height will approximate itself based on grip width for the

lats and hamstrings to “lock-in” isometrically). Further, to

attempt to mimic your actual snatch would violate the analysis and

evidence that suggests training should not mimic sports practice.

That analysis, germane to this topic, is discussed in The Two-Factor Model of Sports Performance. In other words, we are doing the snatch-grip deadlift to get stronger,

not to practice a snatch.

Approach the bar and do

your 5-step-setup for the deadlift. In step 2, take a grip on the bar

that is wider than your conventional deadlift grip width. It needs to

be wide, but not necessarily your snatch grip width. If it is, fine.

Whatever it is, it needs to be consistent. Then finish the last 3

deadlift setup steps. Do this and you will have done a successful

snatch-grip deadlift. But it is going to be vastly different from

your conventional deadlift in important ways.

Rewind to step 1: the

stance. The bottom position of the snatch and snatch-grip

deadlift manipulates your anatomical angles in uncomfortable ways.

You are going to have to have your back angle more horizontal and hip

angle more closed, and therefore more of your torso between your

legs. To facilitate this you might have to do one or a combination of

the following: turn your toes out more so you can point your knees

out, angling your femurs out more, thereby making more room between

the thighs. Or you can take a wider stance with feet at the same

angle as your conventional deadlift– also putting more room between

your thighs. With toes out more the adductors will be more extended,

as opposed to the with wider stance, tightening the hip capsule.

Both of these in

combination are probably unnecessary unless you have some

physiological characteristics that deem it necessary, such as a big

gut or decrepitude; and even so, both in combination may cause some

interesting sensations medially in the adductors near their

origination at the pubis and ischium, as well as laterally in the

psoas, iliacus, and tensor fasciae latae. Irritation in this area can

cause unwanted deviations in training progress, so take heed: The Active Hip 2.0.

Either way, wear tall socks, because the toes-out stance or the wide

stance means a date between your shins and the knurling – and blood

is awfully inconvenient to clean off of barbells. A straight bar-path

and the correct pulling mechanics are the immediate remedy for this,

but it takes some practice with these stances. I have seen athletes

attempt to use shin-guards to remedy grating their shins, but this

fixes something that ought otherwise be fixed with proper technique.

If shin-guards are how you keep your shins from being bloodied, then

there is something wrong with your setup and how you deadlift.

Step 2 is where the

mechanics of the situation are brought to bear. The width at which

you take your grip determines the final height of the hips in the

setup, and for that reason the hip and knee angles when the shins

come to the bar in step 3. A narrow grip means more closed knees and

open hips. A wider grip means the opposite. With the snatch-grip,

there will be more range of motion about the hip joint and less

around the knee joint than in the conventional deadlift.

Step 4, setting your

back in rigid extension, will be harder to do because of the new

anatomical angles necessitated by the grip width. The wider grip

width will have, effectively, shortened your arms. This means that

you will have to have a more horizontal back angle than in your

conventional deadlift. So setting your back will require more

attention and probably discomfort. The toes-out/knees-out stance will

assist in this difficulty.

The landmarks of this

variation will be the same as in the deadlift with respect to the

vertical bar vector, mid-foot balance, and the scapulae. The bar will

still begin over mid-foot and under the scapulae and shins will be

inclined about 7 degrees. The resultant exercise is one that

challenges your will in the setup, demanding hard contraction of the

lats, then taking your hips through a longer range of motion. And at

lockout the bar will be higher on your thighs, demonstrating a longer

bar path than the conventional deadlift as a result of these

intentional variations.

The Deficit Deadlift

Like the snatch-grip deadlift, the deficit deadlift increases the

range of motion of the bar path, but rather than artificially

shortening the arms, it appears as if it lengthens the shank and

femur segments. That is, if the bar is over mid-foot with a deficit –

a block under your feet lifting your stance off the ground – then

the relative shin angle would be very different with longer shins as

opposed to starting with the bar lower on the shins with the bar

closer to the ankle. If you have very very long shins, for

example, and the bar is set up over mid-foot with the bar under the

scapulae then your shin angle would be more vertical than it would be

if the bar started lower on your shins as a result of the deficit.

Think about what your

shin angle would have to be if the deficit put the bar just on top of

your foot— the shin angle would be quite horizontal, comparatively

speaking. So the deficit does not necessarily increase the shin

length; it puts the bar lower on your shins, bringing the bar closer

to the ankle joint, and therefore changing the ratio of upper to

lower segment lengths moving through space. It changes the ratio of

the respective ranges of motion of the segment lengths moving through

space above versus below the hip. The deficit deadlift essentially

puts platforms on the feet, raising the ankle joint off the floor and

allowing for more dorsiflexion.

This mechanical

manipulation comes to bear in the setup. And like the chosen grip

width in the snatch-grip deadlift, the amount of platform block you

choose to use in the deficit deadlift is arbitrary. But we should

exercise some prudence. I like to use a 25-lb bumper plate, which is

about 1.5″ in width. The limiting factor in choosing the amount

of deficit might be what you can reach with your hands while

maintaining your back in rigid extension.

Consider the squat as a

comparison: just as correct depth in a squat can have some minute

variation within reason as long as lumbar extension and knee

positioning remain correct. A too-deep squat might easily be

characterized as knees that have traveled too far forward potentially

accompanied with lumbar flexion/posterior pelvic tilt. This just

amounts to a shortening of the hamstring from the proximal joint (the

hips) and a continued shortening of the hamstring from the distal

joint (the knee).

If one can get into a

very deep squat, deeper than just below parallel and maintain a

neutral lumbar spine and knee positioning, then that excess depth

would be unnecessary and less effective for getting more weight onto

the bar, thereby getting you less strong. But the deficit deadlift

violates the movement choice criteria in just this way, since that is

what it is designed to do.

To set this up, you will approach the barbell as you would a

conventional deadlift, with your toes slightly turned out and shins

1″ from the barbell, so that the barbell is over mid-foot. If

you need a wider stance due to physiological limitations, then you

might need to have 2 bumper plates side-by-side. Step 3 will feel

very strange as you will bend over more at the waist than you are

used to in order to grab the bar since it is farther away. Take your

normal grip.

Step 3, squatting down

to the bar/bringing your shins to the bar will mean bending the knee

more than in a conventional deadlift, since the bar is 1.5″ lower on the shin and the shin will be angled more than the standard

7 degrees due to the increased dorsiflexion. This puts more range of

motion about the knee than in either the snatch-grip or conventional

deadlift. Depending on limb lengths, the hip will also go through a

longer range of motion than the snatch-grip and conventional

deadlift, since the hips begin lower too.

The rest of the

movement is the same as the conventional deadlift. Setting your back

in step 4 is hard, but should be doable if you have chosen the

correct deficit height, and the

back angle will be more vertical. And pushing the floor down

to extend the knees in step 5 will take longer since the bar will

also be going through a longer path.

Anthropometrically

speaking, the bar still begins over mid-foot and underneath the

scapulae. This new exercise will challenge you through what will feel

like a very long way to travel with the barbell off of the floor. It

can encourage you to learn to push harder with the knees to initiate

the first part of the pull, which is a hallmark of the conventional

deadlift, but is by no means necessary, nor the best way to teach the

first push.

Although both of these

variations can increase the size of the arsenal for any good athlete

or coach, they can easily be crutches for the neophyte, using them to

fix movement patterns occurring in the parent movement. Stick with

the parent movement if there is a deviation within that movement. You

can get impressively heavy deadlifts using simple variations (see the

halting and the rack pull). If, on the other hand, you are trying to

introduce a new, light pulling option, then these are novel tools

that can keep training fresh and a little more interesting. But if by

more interesting you are thinking of doing a snatch-grip deficit

deadlift (I have no-shit seen this) because you think more always

equals more, then you are better off getting your deadlift to 600

first. That is much more interesting.

Credit : Source Post